Profile of an adventurer

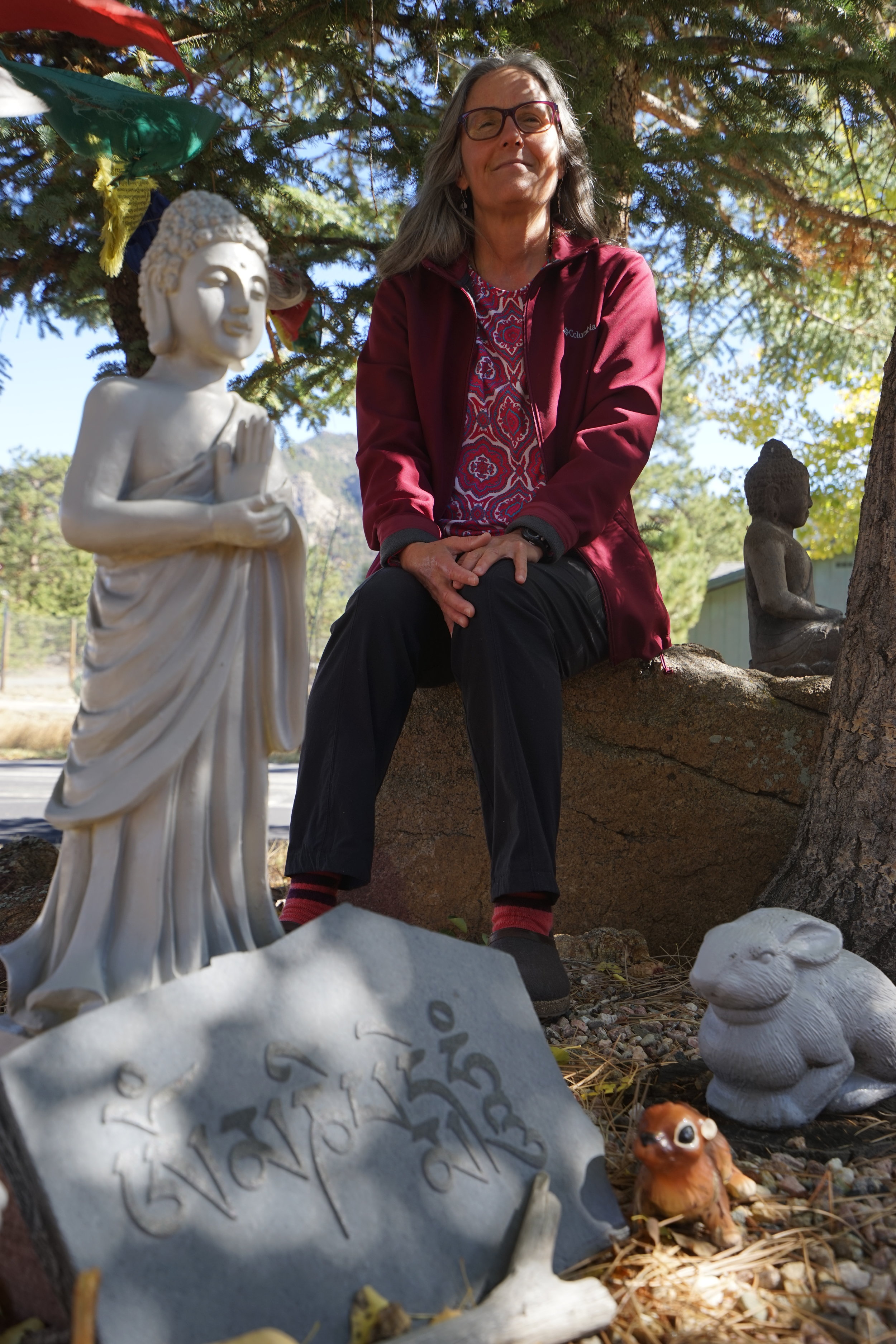

Jean Muenchrath behind her home in Estes Park. Longs peak appears in the background. Photo by Jenna Sampson

A life-threatening fall down Mt Whitney creates a passion for mental strength

Jean Muenchrath’s internal dialogue began while she was laying in a tent on the brink of death.

“If I live until morning I will live all my most important dreams.” Jean repeated to herself.

She was stuck on California’s highest peak, Mt. Whitney. Her repeated thought had five days to calcify into a life-saving mantra as she waited out a storm and made her way to safety. But that was just the start of her story.

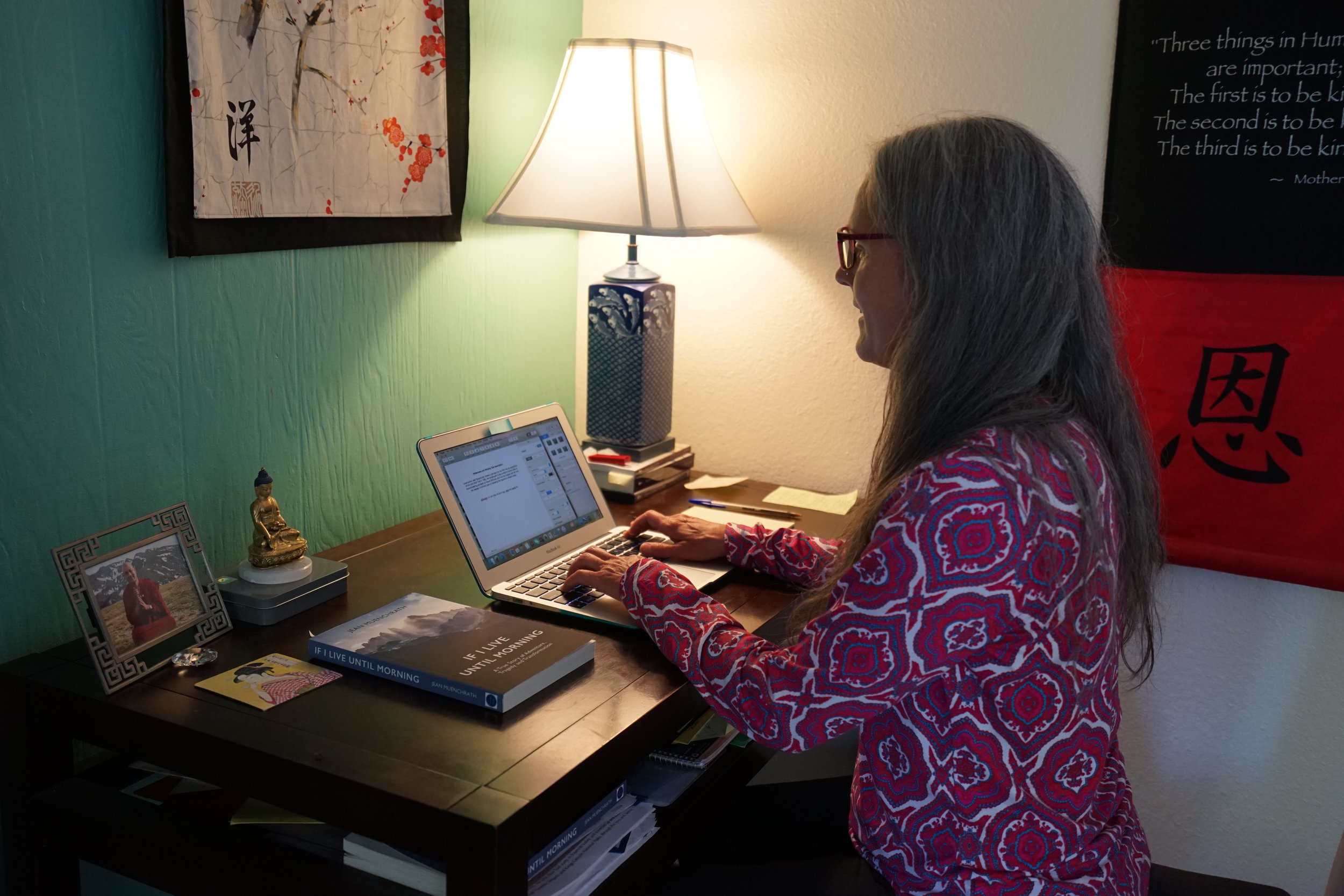

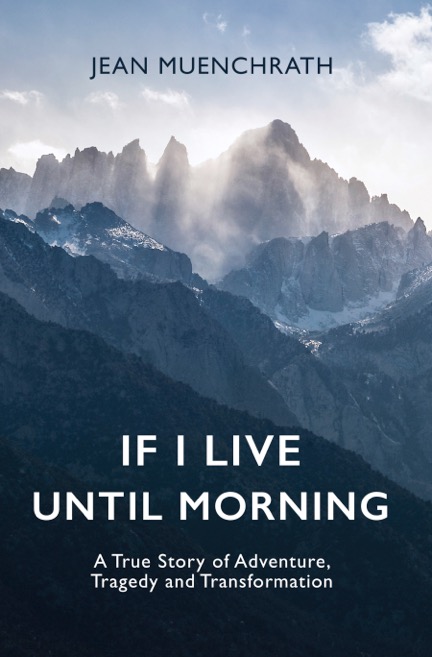

In her self-published book “If I live until morning” Muenchrath takes readers back to her early 20s in 1982 when, capping off a rare winter traverse of the John Muir Trail, she climbed Mt. Whitney. But in her rush to descend during the storm she fell down a rock face on the steep North side of the mountain. In the book she details a story that goes deeper than just a sequence of remarkable mountaineering mishaps. The tale extends to her lifelong quest to make peace with the chronic pain and emotional trauma left behind from the accident by developing a practice of meditation.

Mt. Whitney left Jean with a laundry list of injuries, any one of which would be severe enough by itself to warrant concern. Doctors found nerve damage to her bladder and thighs, a hematoma covering her left buttock with a large area of gangrene, a displaced sacrum, four fractured vertebrae, and a shattered tailbone. Not to mention minor frostbite on her toes, a concussion, and fractures to her pubic bone and hip.

The dream that drove her to survive was to visit the Himalaya, which she accomplished not long after her brutal recovery.

“It took me everything to get to the Himalaya.” Jean explained from the couch in her home in Estes Park, glancing out the window at her towering neighbor, Longs Peak. “I think I want my ashes spread there...”

Jean is a petite woman with long grey locks and a palpable instinct of determination. Her speech is scattered with Buddhist ideas. She says things like “aging is a gift” and “westerners have a different definition of enlightenment.” In her modest home the guest room has been overtaken by a meditation space where the walls are filled with Sanskrit prayers and a shrine to Buddha. Just standing in the small space you can feel the incense and the yellow silk tapestry permeate your muscles and ease you into a mindful state.

In her hospital bed with only a morphine drip to keep her company, Jean wrote a letter to her friend Leanne Benton detailing the entire saga. The two only met at a map making class not long before, but she was the chosen one to receive such an important correspondence. Today they call each other “my dearest friend” and Benton is still in awe of Jean for her determination.

“She comes across as so fearless,” said Benton. “Only about 10 years ago she was at an all time physical low and I got a message from her asking if I could come put her dinner in the microwave.”

It was around then that Jean made an offer to her now partner Paul. He was out of cash from travel and needed a place to stay. He could use her spare room if he promised to take care of her. Since then, Benton said, Jean has transformed.

Every summer she makes a pilgrimage to the Drikung Kyobpa Choling center in Escondido, California to live in silence and study Tibetan meditation for two months. Once the silence begins, she spends each day working on mental strength. Such as redefining the pain and emotion that arise in her mind as things to observe, like clouds passing overhead, instead of issues to combat. Throughout the retreat she can communicate with nuns who run errands for fresh food or laundry via a written instruction left in the window. Paul, who is often there as well on his own retreat, sits by her side for meals.

“I enjoy the intimacy of silence very much,” said Paul. “It’s amazing how much can be effectively communicated nonverbally when both people are attuned and paying attention. Conventional interactions can feel coarse and ineffective by comparison.”

Despite all she’s been through, Jean works as a ranger at Rocky Mountain National Park. Of all national parks, this one has the third most active search and rescue team in the country where almost every other day a new SAR operation takes place. But to her it’s about protecting a place that an increasing number of people need to stay sane, whether they know it or not.

“When I ask park visitors ‘what are you here for’ they can’t articulate it on a deep level.” she said.

Today Jean appears fully mobile and without pain, but her pursuits are dampened by limitation. Due to continued issues with her sacrum, she can’t carry more than a 20 pound load on her back. This makes long-distance trekking difficult.

“Fortunately I still have a strong back and a love for getting Jean into her native habitat of the alpine backcountry,” said Paul. “So if we can’t get a mule or stay in a hut, I am committed to be her porter.”

Jean’s aspirations to travel through the mountains endures. Next she wants to circumambulate Mount Kailas in Western Tibet, also known as Meru, a sacred place for Tibetan Buddhists. The route travels over 30 miles with a high point of over 18,000 feet.

Both Paul and Jean’s beloved chiropractor have their work cut out for them.